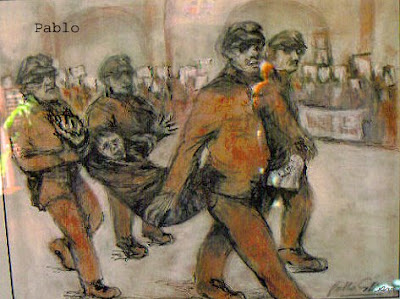

The 9/11 Report: A Graphic Adaptation turns the 9/11 Commission report, the findings of the bipartisan committee appointed by the President, into a graphic novel. It takes the events, the testimonies, and the time lines of the terrorist events and puts them into a comic book format. The graphic novel amounts to a pastiche of the elements included in the report and images deriving from both the artist's imagination and ones mediated by broadcast and print media coverage from both the day of the attacks and political figures of the time. I want to think through what the effect is of putting the report into this aesthetic realm. Turning it into a comic should open the discussion of 9/11 to new audiences, but does it have the effect of reopening the tragedy to new interpretations?

If viewed as a reopening of the discussion, the novel can be seen as an ethical endeavor to further understandings of the tragedy. Consequently, readers may have a new engagement with the event that offers the opportunity for new responses to be formulated from a position of heightened knowledge and the awareness of diverse perspectives. However, by channeling such familiar images, mostly from media coverage, does it simply reinforce existing sentiments? The project mimics the goal of the 9/11 Commission Report, a book that attempted to report rather than engage with the event. But as a work of art, is not the burden one step further, to engage the event, rethink it, ask new questions? I don't know that the graphic novel has this impact.

If viewed as a reopening of the discussion, the novel can be seen as an ethical endeavor to further understandings of the tragedy. Consequently, readers may have a new engagement with the event that offers the opportunity for new responses to be formulated from a position of heightened knowledge and the awareness of diverse perspectives. However, by channeling such familiar images, mostly from media coverage, does it simply reinforce existing sentiments? The project mimics the goal of the 9/11 Commission Report, a book that attempted to report rather than engage with the event. But as a work of art, is not the burden one step further, to engage the event, rethink it, ask new questions? I don't know that the graphic novel has this impact.